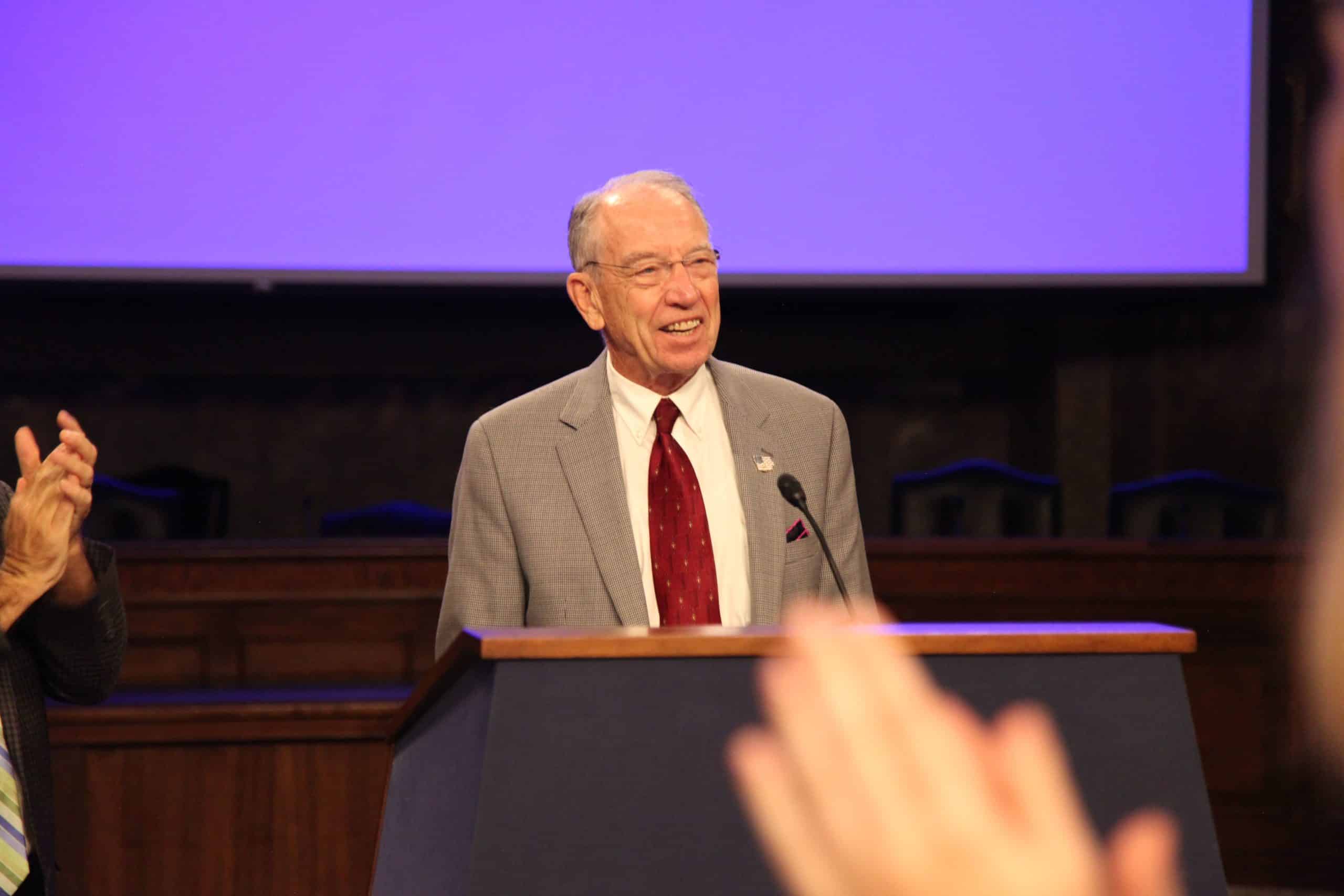

Sen. Grassley Vehemently Opposes DOJ’s Stance on Dismissal Authority Under False Claims Act

On May 4, Senator Charles Grassley, the original author of the revolutionary 1986 amendments to the False Claims Act (“FCA”) and longtime champion of the FCA’s worth as “the government’s most powerful tool in deterring fraud and recovering federal funds lost to fraud,” sent a letter to Attorney General William P. Barr in response to the Department of Justice’s (“DOJ”) current position regarding dismissals of qui tam FCA complaints. In a brief filed against a certiorari petition before the Supreme Court, Solicitor General Noel J. Francisco argued that DOJ’s “dismissal authority of a qui tam False Claims Act case is an unreviewable exercise of prosecutorial authority” because “the plain language of the law grants [DOJ] unfettered discretion in the dismissal of such claims.” Senator Grassley informed Attorney General Barr that he “vehemently disagree[s] with the Department’s reading of the law” and emphasized that acceptance of DOJ’s reading would “create a chilling effect on future whistleblowers that will ultimately end up costing the taxpayers a lot more.”

Qui tam FCA cases are brought by private individuals, known as relators, on behalf of the United States to recoup taxpayer dollars allegedly paid out as the result of fraud. Once a case is filed, the government has a period of time to investigate the claims and decide whether to “intervene” (i.e., take over the primary litigation responsibilities of the case) or decline to intervene. Upon a declination by the government, the case proceeds with the relator maintaining control of the litigation. Senator Grassley pointed out that before 2018, the government rarely sought to dismiss qui tam FCA cases. On January 10, 2018, a DOJ memorandum, issued by Michael D. Granston, Director of the Commercial Litigation Branch, provided new guidelines for the government regarding such dismissals. Ever since this memo, DOJ’s efforts to seek dismissals of qui tam FCA cases have skyrocketed, and “DOJ has moved to dismiss approximately 45 cases pursuant to authority contained in the FCA under 31 U.S.C. § 3720(c)(2)(A).”

As explained by Senator Grassley, in seeking these dismissals, DOJ has claimed, and some courts have agreed, that it “possesses unfettered discretion to dismiss a case over the objections of the relator.” The relevant provision of the FCA provides:

The Government may dismiss the action notwithstanding the objections of the person initiating the action if the person has been notified by the Government of the filing of the motion and the court has provided the person with an opportunity for a hearing on the motion.

In the case at issue here, United States ex rel. Schneider v. JPMorgan Chase, N.A., DOJ contended that under this provision “a hearing does not impose any substantive limitations on the government’s dismissal authority and simply requires that the court grant the relator an opportunity to ‘be heard.’” The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with DOJ and, as phrased by Senator Grassley, found “that the purpose of a hearing in this context is to grant the relator an opportunity to publicly persuade DOJ to change course” and it does not mean an actual judicial proceeding with a judge making a final determination. The Supreme Court denied the petition to review this decision. Senator Grassley, who, again, was the main author of this provision, told Attorney General Barr that “I can confidently say this narrow reading of the False Claims Act is erroneous and contrary to congressional intent.” Senator Grassley further wrote that “the statutory cannons [sic] of construction support the notion that hearing implies an adjudicative procedure where the court acts as an arbiter.”

A twofold argument supported Senator Grassley’s rebuttal to DOJ’s stance. First, he argued that “[b]oth the ordinary meaning and technical meaning of the word ‘hearing’ denote a proceeding which a judge makes a determination based on evidence and the law.” Relying on well-established canons of statutory interpretation and citing to former Supreme Court Justices Antonin Scalia and Felix Frankfurter, Senator Grassley explained that statutory words should be read “according to their ordinary, everyday meanings – unless the context indicates the word carries a technical meaning.” While the term “hearing” has multiple meanings in everyday language, Senator Grassley argued that in the legal field “it is commonly understood to mean a proceeding in which a judge makes a determination based on arguments or evidence presented by the parties,” a definition backed up by Black’s Law Dictionary. This provision was drafted by members of the Senate Judiciary Committee who “are primarily lawyers who also employ lawyers on their staffs—all of whom have a common understanding of the legal meaning of ‘hearing,’” Senator Grassley believes applying such a definition is appropriate.

Senator Grassley furthered his argument on the plain meaning of “hearing,” by writing that even to the vast majority of Americans, “[i]n the context of a court proceeding, the term ‘hearing’ immediately brings to mind a proceeding where a judge decides issues of fact or law,” such as when a citizen is summoned to a hearing for a traffic violation or when a judge ultimately decides the issue of bail in a criminal case after hearing arguments from both sides. Finally, Senator Grassley highlighted that if Congress intended that the meaning of hearing, as advanced by DOJ, was simply an “opportunity to be heard,” it “would have used those exact words as it has done in other statutes.” More broadly, if Congress wanted DOJ to have the unfettered dismissal authority it seeks here, Congress would have omitted the word “hearing” from the statute entirely.

The second prong of Senator Grassley’s legal argument relied on another canon of statutory canon which provides that the wording of a particular provision of a statute must not be read in isolation but rather “in the context of the entire text of the law,” to ensure the “text is in harmony with other provisions in the same law.” Senator Grassley emphasized that the rest of the FCA was not written to provide DOJ unfettered dismissal authority. Instead, Congress “wrote the law to ensure DOJ could not unilaterally dismiss cases.” One such example is that the FCA requires a showing of “good cause” if the government wants to intervene in a qui tam case after the deadline to do so has passed if the relator is proceeding with the case. It would make little sense, according to Senator Grassley, “that Congress would require DOJ to show good cause for intervening but grant them unfettered discretion for dismissing a case they have not yet joined.” Additionally, argued Senator Grassley, allowing unfettered dismissal authority would undermine the FCA provision, 31 U.S.C. § 3730(b)(1), which provides that “a relator may only dismiss a claim if the court and the Attorney General give written consent.” Senator Grassley provided the following hypothetical to illustrate the discord between FCA provisions if DOJ’s argument on dismissal authority is accepted:

Hypothetically, let’s assume a relator moves to dismiss a claim with DOJ’s consent. Under the (b)(l) provision, the court must also consent. Now, let’s assume the court withholds its consent and requires the suit to proceed. DOJ would only need to issue a motion to dismiss themselves, and under the standard DOJ is advocating for, they would have unfettered discretion to override the court’s previous ruling. In this hypothetical case, DOJ would clearly be undermining the judicial branch.

Following his legal arguments, Senator Grassley closed his letter by denouncing “activist judges and career bureaucrats who attempt to undermine Congress’ authority by reading legislative text to achieve desired outcomes in lieu of how the text reads,” implying that is what he believes is occurring here. Senator Grassley further claimed that this position against “activist judges and career bureaucrats” has been publicly supported by Attorney General Barr and President Trump’s administration. Senator Grassley urged the Attorney General to “reconsider the Department’s stance on dismissal authority in light of the overwhelming evidence that ‘hearing’ indicates Congress intended a substantive process in which a judge hears arguments and decides whether a case should proceed or not.”

In his letter’s conclusion, Senator Grassley again trumpeted the brave and pivotal role whistleblowers play in recovering billions of dollars for American taxpayers under the FCA. According to Senator Grassley, Congress fully appreciated the “large investment in time and money” relators expend on behalf of the government in non-intervened qui tam FCA cases (which have recovered $2.4 billion for the government) and because of this investment, “Congress did not grant DOJ unfettered discretion to dismiss a relator’s claim.” Finally, Senator Grassley wrote that “[t]he very fact that a relator can proceed on their own shows that Congress intended for whistleblowers to play a very significant role, and it is partly what encourages reports of wrongdoing.”

Following the letter’s formal conclusion, Senator Grassley also included a powerful endorsement of the FCA through the following handwritten postscript to Attorney General Barr:

Bill: I appreciate that you changed your mind in the constitutionality of the False Claims Act between 1992 and your confirmation to your present position.

But, there are other ways to neuter good legislation even if its constitutional.

I don’t know the number of times the courts have ruled, or DOJ did something harmful, to carrying out the spirit of the False Claims. And, thank God, I, or Senator [Patrick] Leahy, have been successful passing legislation to correct such judicial administrative mal-interpretation.

DOJ’s action of Granston [memo] is just one more example, don’t do hurtful actions to a very successful piece of legislation again. Successful??: Its returned $63 B[illion] to the treasury, yes, successful!!

Latest News & Insights

January 27, 2026