OECD Report Reveals Deficiencies in South Africa’s Anti-Corruption Efforts

A recent report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that South Africa’s efforts to combat corruption are inadequate. South Africa’s implementation of the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (Anti-Bribery Convention) was assessed in OECD’s June 2025 Phase 4 Report. The evaluation focused on three themes: “detection…enforcement of the evaluated Party’s foreign bribery offence, [and] corporate liability” (11).

A recent coup led to the destabilization and maladministration of South African society. Consequently, South Africa underwent a period of state capture, in which the country was systematically dominated by private interests that manipulated policies for private gain. This infiltration of the South African government from 2005 to 2018 inevitably weakened enforcement and allowed both transnational and domestic corruption to flourish. The public and business sectors at national, provincial, and municipal levels were affected, as stated in the OECD’s phase 3 audit: “[whistleblowing] had reportedly declined by more than half between 2007 and 2014” (39). Corruption increases as whistleblowing declines, so while South Africa makes a lethargic effort to combat these abuses, improvements are incremental and few in the foreign bribery sector.

Zero Sanctions

There have been no imposed sanctions or convictions for foreign bribery yet. During the OECD’s third audit, of the ten total cases, six were “closed without charges,” and “only four investigations” remain ongoing (15). This statistic casts doubt on the efficacy and authenticity of both South Africa’s judicial system and its current anti-corruption legislation.

The first foreign bribery case was brought to court in 2019, and progress seemed hopeful until the accused mysteriously passed away before trial; the cause of death is unknown. Referred to as the ‘Telecoms Case’ by OECD, the case concerned a Mobile Telecommunications Network (MTN) company that allegedly bribed “senior Iranian officials” through an “intermediary who was, at the time, South Africa’s Ambassador to Iran” (15). Even after the scheme was publicized by one of the company’s managers, South African authorities concluded the evidence was insufficient to charge the company or any of its employees and instead charged the alleged intermediary. Once the alleged intermediary died, however, the authorities chose not to seize any of the company’s assets, which were believed to be the proceeds of corruption. The utter failure to discipline the perpetrators further illustrates South Africa’s inclination to recede from, rather than combat, foreign bribery and aggravated fraud.

International Cooperation

Despite South Africa’s dereliction in the Telecoms Case, South Africa has notably “helped other Parties to the [Anti-Bribery] Convention conclude their own foreign bribery cases implicating South African public officials” (8). But, write the auditors, South Africa’s compliance with other nations after being found guilty merely chops off a singular “bad branch,” rather than the internal roots of their corruption.

The country is continuously left vulnerable if its legislation cannot support its efforts to eradicate corruption. Even the African Renaissance and International Cooperation Fund (ARF)’s Amendment Bill, which would establish the South African Development Partnership Agency (SADPA), remains “under review” with no updated status or implementation timeframe. When audited by the OECD, South Africa “did not provide any information on awareness-raising activities or evidence that the ARF considers the company’s internal controls, ethics, or compliance” programs during the process of granting Official Development Assistance (OAD) contracts (28). Typically, OADs should include anti-bribery and corruption clauses, and unfortunately, no contracts with such clauses were provided by South Africa either.

Current Framework

OECD described South Africa’s framework as “quite broad on paper” and cause for “concern,” especially given the lack of company accountability, the “low number of investigations,” and the growing “alleged political interference” (8,75). Although a broader framework would typically allow for more prosecutions, legislation’s reach is hindered by insufficient investigative efforts.

Combined with a lack of anti-corruption training and the absence of any foreign bribery cases detected, the OECD raised concerns about “South Africa’s ability to identify money laundering predicated on foreign bribery” (32). Accordingly, self-reporting cannot occur properly without the education or the means to do so.

The Deaths of Self-Reporting and People

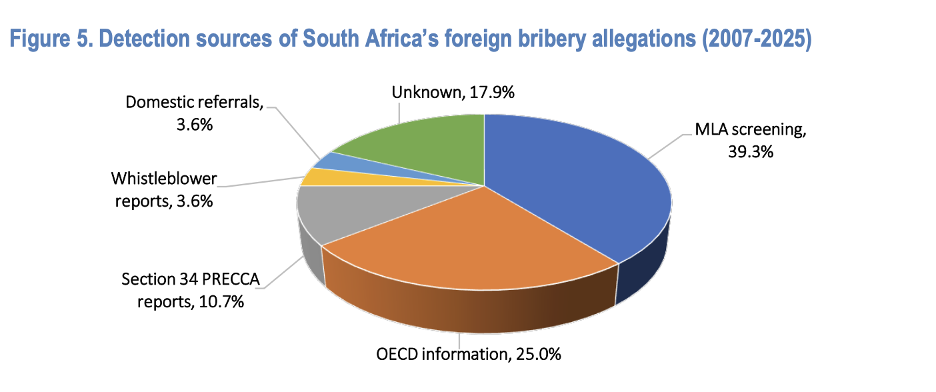

A crucial source for detecting foreign bribery has been neglected. According to a 2017 OECD study on worldwide methodologies for detecting and prosecuting foreign bribery, nearly one-fourth of global foreign bribery cases that resulted in sanctions were discovered when a company self-disclosed the wrongdoing to law enforcement authorities. This pattern does not hold in South Africa: there have been no sanctions at all. It is clear that 25% of potentially detectable corruption is currently going unreported by companies that may otherwise have been incentivized to report it. The auditors write, “South Africa has no formal legislation specifically designed to require or encourage companies to self-report foreign bribery” (35).

Despite the lack of formal anti-corruption training for employees, South Africa’s Asset Forfeiture Unit (AFU) established a corporate Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) process to encourage self-reporting. However, the agency has yet to achieve its stated goals due to broader reluctance to report.

In a 2024 survey of South African public officials, more than half (53%) observed misconduct, yet fewer than half (40%) reported it, largely due to concerns about confidentiality and retaliation. The same survey shows that the most common reason for not reporting was the belief that doing so would not make a difference (86%), with other reasons including fear of confidentiality (81%), victimisation (81%), dismissal (58%), safety (57%), and being fearful of their own life (48%) or for one’s family (42%).

Fear for their lives and physical safety may be deterring potential whistleblowers. This fear is not unfounded: “In some cases, whistleblowers have been killed” (39).

Pamela Mabini was shot and killed outside of her home, while other South African whistleblowers were arrested with delusive charges, suspended from work, or forced to relocate abroad. If whistleblowing comes at the cost of one’s life, it is understandable why one might be so fearful of reporting. Thus, South African legislation must begin to include stronger protections against retaliation and rewards for informants, so that the advantages of reporting outweigh any disadvantages.

Suspiciously High Levels of Public Ownership

South Africa’s high level of public ownership creates substantial structural vulnerabilities in its anti-corruption framework, as economic power is concentrated in politically exposed, procurement-intensive industries. This increases the risk of foreign bribery, reduces accountability, and creates a greater potential for improper influence. At the national level alone, there are “40 [State-Owned Enterprises], mostly in high-risk industries such as defence, energy, oil and gas, telecommunications, and infrastructure” (13–14).

The composition of South Africa’s small and medium enterprises (SMEs) within the business sector exacerbates these concerns. In 2022, only “37% of the estimated 2.6 million SMEs” were formal businesses, while 66% had no employees and another 32% employed between one and ten people (14). This highly unofficial and dispersed environment closely resembles traits often associated with shell corporations, including low staffing, limited physical presence, and a lack of official registration or regulatory oversight.

34 PRECCA Report Against Corruption

As of May 2025, only one foreign bribery allegation was detected through a whistleblower report. Reporting is made possible through section 34(1) of PRECCA which “obliges natural persons holding a position of authority to report certain corruption-related offences” or through the Public Service Regulations (PSR) which “requires all public servants to report corruption” to their “head of department” under regulations 13(e) and 14(q) who, in turn, “must make a section 34 PRECCA report” (20-21). This bureaucratic and labyrinthine requirement to report corruption through one’s higher-ups or employer一who may themselves be complicit in criminality一makes it no surprise that no cases have been detected through PSR reporting. Further still, seeking management’s approval to report bribery and corruption may leave whistleblowers vulnerable to retaliation. Especially as infamous stories have circulated revolving around the chilling murders of previous whistleblowers, the incentives to report are slim to none.

(Figure 5. Detection sources of South Africa’s foreign bribery allegations (2007-2025). OECD Phase 4 South Africa Report, p. 20)

Fragmented Progression

Despite these ongoing difficulties, there have been some small wins in the anti-corruption realm. By allowing companies to avoid prosecution through the fulfillment of certain conditions, the ADR shows the AFU’s proactiveness “in seeking ways, with or without conviction, to recover illicit proceeds from corruption offences” (102). This coincides with an enhancement of the screening process to detect foreign bribery. By adopting a formal mechanism, unnamed by the OECD, South African authorities can better screen incoming Mutual Legal Assistance (MLA) Requests to detect cases of potential foreign bribery.

A concerning divergence in priorities is evident in the gap between the overall rise in the workforce and the decrease in anti-corruption staffing. The South African Police Service (SAPS)’s total workforce has even increased from 501 individuals in 2015 to 2,831 in 2024, yet the “number of staff assigned to serious corruption cases declined from 84 to 76” (57). Especially as South Africa is in a post-state capture period, greater institutional commitment is required.

Overall, the whistleblowing climate remains challenging due to limitations in current legislation and the lack of safeguards to protect whistleblowers from retaliation. Part of this challenge lies in the fragmented resources dispersed across a multitude of agencies, each with its own different reporting channels. According to the report, “One public sector official reported identifying at least 38 separate agencies with some responsibility for whistleblower issues” (39). An inconsistent and ununified system discourages individuals from coming forward.

Enhancing Legal Protections

South Africa’s current structure for enabling and protecting whistleblowers is enfeebled by restrictive laws. Under the Protected Disclosure Act (PDA), “the whistleblower must satisfy specific conditions for each channel to qualify for protection,” and disclosures made through any alternative avenue are protected only if made “in good faith” (41). Courts interpret good faith through the reasonableness of the whistleblower’s belief. Yet, this standard is burdensome, especially as whistleblowers reporting foreign bribery “must have a reasonable belief that all information is ‘substantially true’” and must also prove that reporting directly to law enforcement was more reasonable than choosing another channel (42). These cumulative restrictions make it dangerously easy for legal technicalities to be turned against whistleblowers, creating an environment where remaining silent appears safer than confronting corruption.

Lack of Judicial Guidelines

South Africa’s enforcement challenges are compounded by the absence of judicial sentencing guidelines, resulting in inconsistent, unpredictable, and often inequitable outcomes. Although the Criminal Procedure Act grants courts “considerable discretion to select the appropriate sentence,” there are “no guidelines for determining the nature or amount of sanctions that should be applied” (50). Judges themselves reported relying on subjective assessments of personal circumstances, community interests, and comparable cases, while acknowledging that appeals are welcomed simply because appellate rulings provide much-needed clarity. This approach prolongs proceedings, undermines judicial efficiency, and discourages reporting, as “foreign bribery defendants could, in theory, face widely disparate levels of sanctions for the same factual scheme depending on which court sentences them” (51). Such variability places too much power in individual interpretation rather than in a uniform, equitable system.

Although South Africa is still in rebuilding its investigative and prosecutorial capacity following the state capture period, the fact that no corruption cases have been brought to justice is problematic. It’s time for South Africa to enact legislation that ensures justice is served efficiently and effectively while protecting whistleblowers from retaliation.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]Latest News & Insights

November 19, 2025