OECD Report Exposes Brazil’s Weak Anti-Bribery Enforcement

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published its Phase 4 follow-up evaluation of Brazil in October 2023. The report revealed Brazil’s failure to detect or enforce foreign bribery offenses and anti-corruption legislation. Thus, Brazilian prosecutors are forced to report to other nations, primarily the United States, to bring justice for whistleblowers.

Stephen Kohn, one of America’s top whistleblower attorneys, praises these prosecutors: “Brazil’s Federal Prosecutor’s Service (FPS) is in the forefront of exploiting the transnational nature of foreign bribery laws and cooperating with law enforcement agencies outside of Brazil to accomplish some of the largest and most important Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) prosecutions in history.” Still, Brazil’s failure to establish an effective internal oversight structure undermines its own prosecutors.

Map of Countries Allegedly Bribed by Brazil

Almost all successful anti-corruption prosecutions in Brazil have been brought by the United States under its Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA); in three major cases alone, Brazilian companies have paid over $5.34 billion to the US.

Despite being the 13th-largest economy in the world and the 11th-largest in the OECD Working Group by GDP, Brazil performs well below average in anti-corruption enforcement. Thus, the OECD called for stronger measures: “Brazilian authorities have only investigated 28 of the 60 allegations of foreign bribery,” with 49 allegations (81%) “involving 5 companies already charged or sanctioned in relation to foreign bribery” (3). The egregiously high rate of repeat offenders casts doubt on the efficacy of Brazil’s law enforcement and current legal structure, underscoring why prosecutors must seek help elsewhere.

Delayed Justice

“Brazil’s first-ever criminal proceeding, [‘Aircraft Manufacturer’ in 2014], for foreign bribery remains ongoing after nearly a decade,” as it languishes undecided within the Brazilian court system (3). This lack of urgency is clearly far too slow to effectively combat corruption. In a similarly disappointing manner, Brazil has implemented only 18 of the 39 recommendations over the last two years, despite the OECD’s Phase 3 Report being released in 2014.

Corruption Without Consequence

The Brazilian economy is significantly dependent on state-owned enterprises (SOEs). In a 2020 OECD report, out of Brazil’s 203 SOEs, 157 were under the indirect control of the same “five state-owned corporate groups” (8). The corporate structure appears suspicious to OECD auditors, mainly because 52 of the subsidiaries are Petrobras, a Brazilian petroleum company. This means not only that 77% of Brazil’s federal SOEs are indirect, leaving a greater margin for corruption, but also that Petrobras, a company already sanctioned for corruption, owns 33% of those indirect SOEs. For instance, on December 14, 2023, Petrobras was accused by the U.S. Justice Department of receiving millions of dollars through a bribery scheme in the United States of America v. Freepoint Commodities LLC.

Brazil’s top foreign direct investment (FDI) destinations in 2021 featured several state economies with notorious reputations for limited transparency and high levels of corruption. Interestingly, Brazil’s third-largest product export is mineral fuels, a classification that includes all types of fossil fuels. According to OECD, “fossil fuels have been associated with higher foreign bribery risks”, which have already been seen through cases such as Petrobras and Freepoint Commodities LLC (8). Therefore, not only is a large volume of Brazil’s investments occurring in high-risk places, but it’s also occurring within a high-risk trade sector.

Disincentivizing Incentives

As of July 1, 2023, a substantial portion of the 60 total foreign bribery allegations were directed at the Lava Jato operation. The investigation began in 2014 as a money laundering case, but soon revealed itself to be much more. As detailed by the OECD auditors, there was an “extensive pattern of domestic corruption, foreign bribery, and money laundering offenses committed by Brazilian construction companies, foreign multinational enterprises, and a host of corporate executives and employees as well as Brazilian and foreign public officials” (10-11). Thus, corporations (such as Petrobras) and public officials have been implicated in Brazilian corruption, further underscoring the urgent need for anti-corruption laws similar to those in the United States.

Furthermore, the most prominent Brazilian corruption case involved the construction company Odebrecht. This remains the largest ever U.S. FCPA monetary sanction of $3,557,626,137. In this historic case, Odebrecht, a Brazilian conglomerate, admitted that it had “paid over USD 788 million in bribes to public officials, political parties and their officials, or political candidates from Brazil and 11 foreign countries” (11). This case, in combination with the Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. (Petrobras) case, the fourth-highest US sanction at $1,786,673,797, makes it evident that anti-corruption legislation cannot be enforced by officials who are also corrupt. Brazil should emulate the United States Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and create effective anti-corruption legislation, as that would help implement some of the OECD’s Recommendations listed on pages 102-107 of their report.

Ignored Recommendations

While Brazil’s judicial system often fails whistleblowers, some Brazilian legal persons have rightfully sought help in other countries to report corruption. It’s highly concerning that Brazil has yet to achieve a sustainable level of foreign bribery enforcement commensurate with its economic profile, given its accountability for some of the world’s largest corruption cases. One of many flaws in its system derives from the fact that the public sector is unaware of how to report compliance violations in bribery cases. Despite the OECD’s recommendation in Phase 3 (2017) to increase training on “reporting suspicions”, the Brazilian authorities still report “that all their concluded cases resulted from allegations detected through self-reporting.” (14-16). This is more of a compliance tactic, typically use after a company suspects it has been caught, to secure a lesser sanction. As such, self-reporting is much less effective at combating fraud than whistleblower reporting. With underused sources of detection, such as internal whistleblowers, and the majority of public officials being caught in bribery schemes, Brazil will be stuck in the same cycle of corruption. Brazilian self-reporting is done as an act of defense and a prayer for a lesser sanction, rather than a means for citizens or potential whistleblowers to uphold ethical practices.

This lack of effective detection mechanisms extends even to the judiciary. Despite repeated OECD recommendations dating back to Phase 2 in 2010, Brazil has neither provided adequate training nor issued directives to tax auditors and officials. As the OECD report warns, “imprisonment sentences can only be executed after a final unappealable decision” (70), making it extremely difficult to deter offenders. Without judges who understand the complexities of foreign bribery law, sanctions lose meaning. Cases may drag on for years while corruption continues unchecked, as in the ongoing Aircraft Manufacturer case.

Brazil did attempt to incentivize self-reporting by introducing a leniency measure through Normative Ordinance 19/2022, which allows companies to receive lower penalties if they admit wrongdoing and cooperate. However, the OECD found the provision meaningless in practice: “Authorities did not clearly articulate by how much a fine would be reduced if companies self-reported and cooperated” (29). Combined with a “decline in criminal law enforcement in recent years” (29), this ambiguity creates the perfect environment for companies to stay silent.

The Silenced Whistleblower

The legal framework further discourages whistleblowing by failing to protect those who come forward: “Law 12.527/2011 does not expressly provide for confidential reporting, protection from disciplinary or other retaliatory acts within or outside the workplace, or remedies for damages caused by retaliation” (30). The framework also does not provide interim relief to those facing retaliation, nor does it shift the burden of proof onto employers. Without basic safeguards, employees risk their livelihoods for reporting misconduct, effectively silencing potential informants in both public and private sectors.

This inaction has persisted across multiple OECD evaluations. Even the OECD Working Group’s most fundamental recommendations have been neglected for years, prompting the OECD to consider “dropping one [report] concerning the confiscation of bribes that have not been transferred” due to Brazil’s overwhelming backlog of unaddressed issues (42). In the absence of legislative reform, more transparent enforcement procedures, and true protection for whistleblowers, corruption will continue to thrive under Brazil’s lethargic legal system.

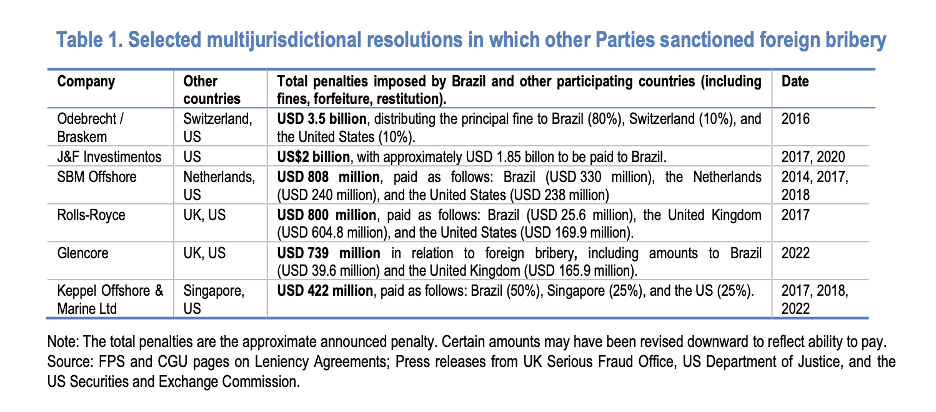

(Table 1. Selected multijurisdictional resolutions in which other Parties sanctioned foreign bribery. OECD Phase 4 Brazil Report, p. 12)

Consequently, as seen in Table 1, Brazil must participate in multijurisdictional resolutions of transnational corruption cases. As of 2016, they have cooperated in at least 12 such cases, “resulting in over USD 9 billion imposed in monetary penalties on the companies,” while Brazil received “approximately USD 5.6 billion of the total amount” due to “working with their counterparts to gather relevant evidence” (12). This is a form of mutually profitable anti-corruption cooperation that should be a worldwide norm.

“Brazil’s highly defective whistleblower laws demonstrate the need for Brazilian whistleblowers to utilize the anonymous, confidential reporting mechanisms available under US law,” said Kohn. “Just as the Brazilian prosecutors have used US law to put teeth behind their investigations, the whistleblowers must do the same. They need to use the law to put real force behind their protections.”

Therefore, there is an urgent need for the UN and participants of the UNCAC convention to promote stronger international whistleblower legislation. Endorsing the enforcement mechanisms that Brazil has successfully utilized to work transnationally with other law enforcement agencies would help prosecute some of the largest bribery cases in history. The National Whistleblower Center embraces these policies, both for law enforcement cooperation and whistleblower protection.

Latest News & Insights

February 24, 2026

February 24, 2026

February 16, 2026