Italy’s Failure to Uphold Anti-Bribery Convention Exposed by OECD Report

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) recent evaluation of Italy’s anti-corruption legislation and enforcement was highly critical. The report, a Two-Year Follow-Up to the Phase 4 Evaluation of Italy’s Implementation of the Anti-Bribery Convention, exposed Italy’s halfhearted attempts at upholding international legal standards and strongly recommended further action. According to the auditors, “Italy has fully implemented 18 recommendations, partially implemented another 7 and not implemented 23” (Follow-Up, 5). In particular, the report highlighted Italy’s lack of an effective strategy to combat foreign bribery and expressed concern about its shocking decline in enforcement actions.

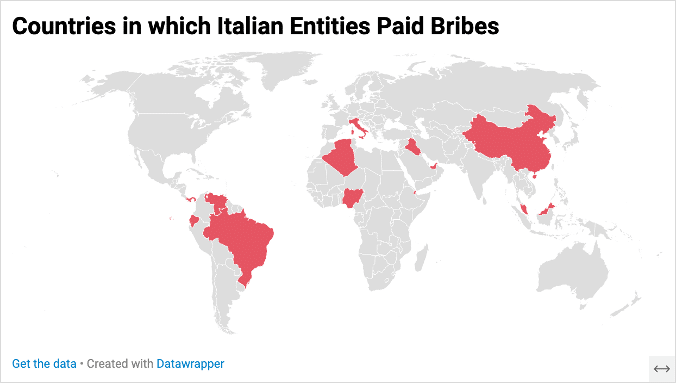

Failure to Prosecute Foreign Bribery

Italy’s legislative structure for detecting, prosecuting, and combating foreign bribery is inadequate, according to the OECD. Although Italy attempted to uphold the Convention via training and awareness raising, “Italy still does not have a comprehensive national strategy to fight foreign bribery which identifies the sectors and activities in Italy that are at risk of foreign bribery, and which specifies measures for addressing those risks” (6).

Furthermore, savvy actors can easily circumvent the existing anti-bribery legislation by exploiting the numerous legal loopholes. These include overly stringent standards for evidence, infeasibly short statutes of limitation, easily manipulated defenses, and paper-tiger punishments.

Almost all successful anti-corruption prosecutions in Italy have been brought by the United States under its Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), as Italy lacks effective internal anti-corruption enforcement; in three major cases alone, Italian companies have paid over $512.5 million to the US.

Onerous Standards

Italy has a high standard of proof in foreign bribery cases, as it systematically rejects circumstantial evidence and requires proof that the foreign law is violated. These standards, argues the 2022 Phase 4 report, “make [foreign bribery] almost unprovable in Italian courts” (Phase 4, 43). The up-to-date Follow-Up makes it clear that Italy has wholly failed to loosen—indeed, even tightened—its overly stringent requirements, leading to an abnormally large proportion of cases ending in dismissal.

According to the report, “requiring proof of foreign law for the foreign bribery offence [is a] clear contravention of Convention Art. 1” (Follow-Up, 5). In a blatant display of apathy towards the international convention, the Italian Supreme Court has long held that courts must enforce a two-branch test to determine guilt in a foreign bribery charge. Essentially, to be convicted in Italian courts, the prosecution must first prove that the conduct was illegal under the laws of the country where the bribery occurred, and second, demonstrate that it was also illegal under Italian law. This lack of an autonomous legal structure for prosecuting bribery is self-evidently ineffectual and outdated.

Regarding the exclusion of circumstantial evidence, the Follow-Up report commended Italy for holding a workshop that “addressed the treatment of circumstantial evidence” (10), but has yet to assess its effectiveness especially since “case law examples provided by Italy [to demonstrate progress] are not relevant to the level of details about the corrupt agreement that must be proven for the foreign bribery offence” (10). Time will tell if Italy’s efforts are fruitful.

Time Obstructed Enforcement

Compounding the already Sisyphean evidentiary requirements are Italy’s egregiously short statutes of limitations and deadlines. Prosecutors must navigate tight timeframes for investigations, as well as conflicting statutes of limitations that apply to both natural and legal persons. This longstanding issue has repeatedly led to the dismissal or discontinuation of corruption and foreign bribery cases.

The report states, “Preliminary investigations in Italy must be concluded within 6 months … Because of this short deadline, however, some prosecutors have been forced to take foreign bribery cases to trial while requests for [mutual legal assistance] were still outstanding” (Follow-Up, 12). These limits are clearly obstructing investigators and authorities from carrying out the law to its fullest extent. There is simply no reason to place hindrances on prosecutors in such a way; the law should facilitate rather than check the authorities’ power to effect justice.

Worse still, “the Working Group has stated that the five-year statute of limitations for legal persons is too short. Many cases have therefore been time-barred” (Follow-Up, 12). The limit for natural persons, on the other hand, is 15 years. This disparity, says the OECD, has led “to unjust situations like in one foreign bribery case where individuals faced prosecution, but the company’s charges were time-barred” (Follow-Up, 13). The disparity can also lead to the unfair scapegoating of one perpetrator, allowing other individuals or companies to continue malpractice unabated.

Effective enforcement of anti-corruption legislation often requires in-depth investigation and lengthy court proceedings. To ensure that both corrupt corporations and individuals are held accountable, prosecutors should not have to race against the clock.

Despite being aware of this problem, Italy appears to have has no plans to rectify it. In fact, recently proposed legislation might aggravate the issue: “The Minister of Justice has reportedly presented a bill to reduce the statute of limitations, including for corruption offences” (Follow-Up, 13). This bill would be counterintuitive to fighting financial crime. From the OECD’s perspective, allowing this legislation to pass would unjustifiably accelerate an already hasty process.

Justice Unserved

A particularly alarming oversight in the Italian prosecutorial system is its overly lenient defense provisions. One, the “defense of effective regret,” is uncommonly lenient: “The offender may escape liability by identifying any ‘other perpetrator’” (Phase 4, 46). The purpose of the defense is to aid authorities in prosecuting other corrupt officials and nationals. If, however, the offender chooses to identify a corrupt foreign official, Italian courts will be unable to prosecute a foreign national; thus, the information will not lead to meaningful enforcement. This procedure entirely negates the purpose of the defense. “‘The crime,’” writes the OECD, “’may come to light, but the offenders remain unpunished and the ends of justice are not served’” (Phase 4, 46).

Despite the Working Group having repeatedly expressed its concerns about the defense of effective regret, “Italy has not taken any steps to implement the recommendations” (Follow-Up, 11).

Another unaddressed loophole is the concussione defense. This provision is doubly impactful, as it applies to both foreign bribery and extradition for foreign bribery. The report describes it thusly: “Concussione takes place when the official coerces an individual ‘by means of violence or – more frequently – threat, explicit or implicit, of an unjust prejudice’” (Phase 4, 44). Uthis definition, the individual does not receive any undue advantage.

Case law, however, raises concerns about the overly broad application of this defense. In a recent case, a company excluded from a transaction bribed foreign officials. The court found that bribery had, in fact, occurred, but that the company was still a victim of concussione. The auditors expressed apprehension about the application of concussione in this case: “This seems to imply that concussione may have been applicable had the company been refused something to which it was entitled” (Phase 4, 44). This application may lead to corrupt actors receiving lower sanctions, even in cases where bribery was blatant, if any concussione has occurred.

In fact, according to the OECD, “These cases also suggest that limited evidence is needed to prove undue inducement and concussione” (Phase 4, 45). There is a worryingly high potential for abuse of this defense.

Regarding extradition, the auditors write, “By raising concussione a person sought for extradition could advance an argument that their conduct does not constitute a criminal offence in Italy because they are a victim of concussione, not a perpetrator of bribery” (Phase 4, 59). This defense would have the dual impact of thwarting justice in Italy and the other state.

Italy provided no information to auditors regarding concussione in the most recent Follow-Up, leading one to believe that there has been little improvement since 2022, when the Phase 4 report was published.

Just the Cost of Doing Business

Even when the embattled prosecutors successfully withstand the deadlines and defenses, Italian enforcement actions are so low as to be inutile. Despite OECD recommendations dating back to 2011, fines for both legal and natural purposes remain “unfit for purpose” (Follow-Up, 5).

Regarding legal persons, “The maximum ‘base’ fines are too low. Many mitigating factors then apply cumulatively to radically reduce the base fine” (Follow-Up,11). Italy claims that it will introduce legislation “soon” that would raise maximum fines. “But this would still result in maximum fines of just EUR 387 800 to EUR 1.55 million for the seven foreign bribery offences. The available mitigating factors would remain unchanged” (Follow-Up, 11). When corruption schemes can generate hundreds of millions, sanctions this low are just the cost of doing business.

Recall that the statute of limitations for natural persons is 15 years, far longer than the five-year limit for legal persons. Unfortunately, Italy thoroughly fails to take advantage of this fact. “Italy is one of only three Working Group countries that cannot impose fines against natural persons for foreign bribery,” (Follow-Up, 11) lament the auditors.

Individuals who commit foreign bribery pay no fines whatsoever. They may face imprisonment and confiscation, but “confiscation for less than [the value of the bribe] was imposed in at least three out of ten post-Phase 3 foreign bribery cases” (Follow-Up, 11). For individual corrupt actors, there is everything to gain and absolutely nothing to lose.

Unprotected Whistleblowers

Coupled with Italy’s lackluster enforcement are its halfhearted whistleblower protections. In 2023, Italy enacted the Whistleblower Protection Law (WPL), which broadly defined the categories of persons who can report and the types of retaliation that are prohibited. Commendably, it includes remedies for retaliation, such as “annulment, reinstatement, and compensation for damages, with reversal of the burden of proof” (Follow-Up, 7). It does not include incentives. Being new legislation, the WPL’s efficacy has yet to be assessed.

Unfortunately, the law only applies to public sector whistleblowers, leaving those in the private sector disincentivized and subject to retaliation. According to the report, “whistleblowers who report foreign bribery or related offences are not protected if their company does not have an ‘organisational model’” (Follow-Up, 7). And if the company does have such a model, whistleblowers are only protected if they report internally and nowhere else. In sum, without a model, whistleblowers are unprotected; with a model, whistleblowers must report directly to the corrupt actors and are thus, again, unprotected.

Sanctions for retaliation exist but are so low as to be insufficient “to deter most senior managers or officials.” Furthermore, “Fines can only be imposed on individuals, not private sector entities” (Follow-Up, 7).

Italy has no award programs whatsoever. Although whistleblower awards are enormously helpful in detecting and deterring corruption, whistleblowers often languish without protection and compensation.

Declining Enforcement and Potential Remedies

Italy’s array of failures is having a noticeable effect on enforcement. The auditors report, “In 2011-2022, Italy recorded 90 investigations, 72 proceedings, and 22 convictions. In the two years since the Phase 4 Report, enforcement has dwindled to just 1 new investigation, no new proceedings, and 4 convictions” (Follow-Up, 5). Corruption appears to be self-propagating: the longer Italy fails to enforce and strengthen its impotent legislation, the more formidable the problem becomes.

Stephen M. Kohn, leading international whistleblower and anti-corruption attorney, said, “The failure of Italy to have a comprehensive strategy to combat corruption is not acceptable.” Kohn continued, “We hope that Italy, in the upcoming UN Anti-Corruption meeting (Cosp 11), strongly supports the National Whistleblower Center [NWC] resolution calling upon increased Foreign Corrupt Practices Act enforcement.”

The NWC, an organization dedicated to promoting the protection and compensation of whistleblowers, will attend the 11th Conference of States Parties (CoSP 11) to the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC).

Italian authorities are aware of what they must do. Having already enacted 18 recommendations as well as the WPL, Italy has the inchoate foundations for strong, healthy governance. All that remains is to act.

Latest News & Insights

February 24, 2026

February 16, 2026